Increasingly, over the past few months, I have been really leaning into examining documents that are in languages I don’t speak.

When you first open up a document and it’s written in another language, it’s easy to let your eyes glaze over as you try to scan for anything familiar, get discouraged by the enormity of the task you are attempting, and give up. But I have good news—you don’t need to learn a whole new language to learn what’s in those documents. You just need to learn how to use a few tools and have a decent amount of patience. It’s not easy, but it’s definitely not impossible, either.

My area of research, Louisiana, became a state only in 1812. It was a French colony in its earliest years; a Spanish colony from 1762-1801; briefly, it was French again; then the United States made the Louisiana Purchase, and the territory was on its way to being permanently American.

Some researchers I have communicated with have indicated to me that they hate doing Louisiana research because of this complicated history and the lack of familiar record sets and repositories for the colonial period. However, I have good news for y’all: France and Spain have both kept amazing records for a very long time, and the governments of those countries seem to be quite dedicated to digitizing their vast archives and making them accessible to all. Additionally, Catholics keep great church records.

The catch is that the records from the Spanish and French colonial periods are, of course, typically in Spanish and French. I want to show you my own process for analyzing these records, and I want to point out some online repositories that weren’t that obvious to find but contain a wealth of documentation relevant to researching in the former colonies of those nations.

I will start with a French repository. I have never formally studied French; I cannot understand spoken French, and I can’t produce my own sentences either out loud or in writing. But I couldn’t let that stop me when so much of what I want to learn is probably written down somewhere in French. And I don’t have time (or the will) to stop what I’m doing and study the language for years.

Enter ANOM, the Archives nationales d'outre-mer. This website has a database of digitized documents from many former French colonies. The website interface itself is in French. That can feel confusing, because you don’t just know what the different buttons and menu items are referring to. That brings me to my first, most obvious and most used tool of choice when working with foreign-language documents: Google Translate.

I know you’ve heard of Google Translate, but it’s quite possible you don’t know just how good it is these days and how much it can do for you. I even use it in many cases on English documents, which I will get to in a bit!

This is the default Google Translate interface:

Notice the red box I have drawn around the tabs at the top. Everyone knows you can enter free text into Google Translate and it will be translated into your language of choice. I don’t think everyone knows that you can wholesale paste screenshots of images into it, or upload documents, or enter in a URL to a web page and have the entire page translated. Well, you can do all of those things! If you use Google Chrome, you can even set up your browser to automatically translate every page you land on into English for you. I have set this up (the browser will ask you if you want to translate pages in [insert language] to English and you just hit “yes”!) So this is the actual interface for ANOM:

And this is what I see now:

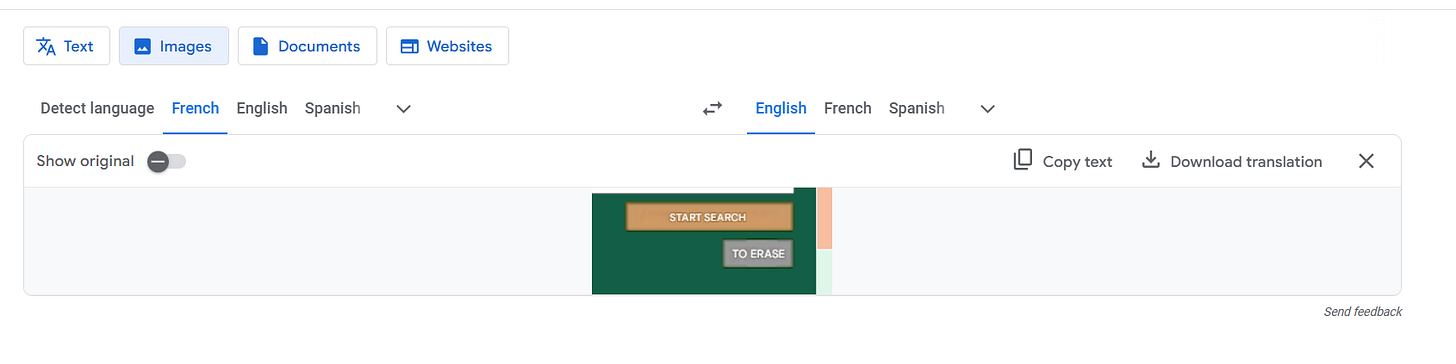

The translation is quite good! It’s understandable, for sure. The parts of the page that did not auto-translate are the parts that are actually made up of images instead of text; the browser doesn’t attempt to analyze and translate what it interprets as a picture, even if that picture is of text. What if I want to know what this says?

I could type that whole phrase into Google Translate, but that’s tedious. Instead, I can take a screen snip (which I already did in order to paste that image into this post) and paste it directly into the “image” tab of Google Translate. This is what that produces:

Bam! “National Overseas Archives”, makes total sense. I did the same thing for the buttons on the search interface.

Now that I know which button means “search” and which one is going to clear out my inputs and reset the search form, I won’t be inclined to continuously hit the wrong one and have to start over. :-)

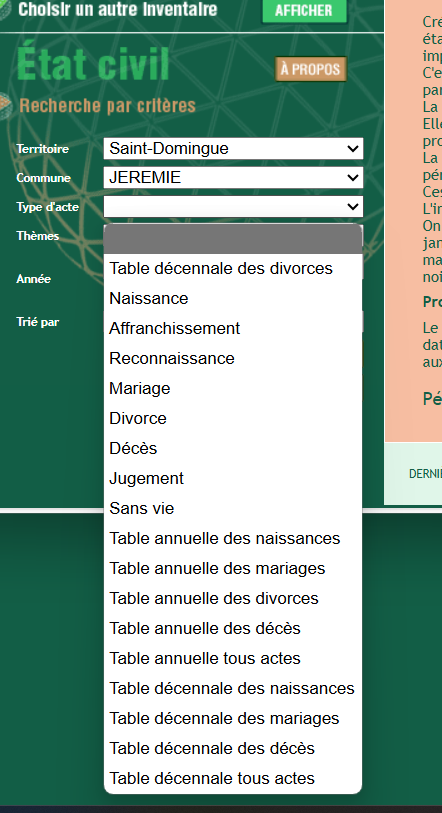

I can select a territory and a town within that territory, which is straightforward enough. But when I look at the dropdown for “types of acts”, if I haven’t got my browser set up to automatically translate, these are my options:

Some of them are pretty obvious. Others are not so obvious. But good news: Chrome will translate the contents of a text dropdown.

That’s better. It’s worth exploring the different kinds of records you can look at in here to get an idea of their organization. I’m going to use a real example from my own research recently, where I wanted to find records of a family in Saint-Domingue who had moved to New Orleans after the Haitian Revolution.

My starting point was a couple of abstracts from the Archdiocese of New Orleans records.

Margarita Adelaida Justina Reyna (Juan Luis ROBIN and Margarita Feliciana CHOMBERG), native of Jeremie on the island of Santo Domingo, m. Juan Pedro ROUX, Jul. 29, 1814 (SLC, M6, 147)

Marguarita Adelaida Justina Reyna (Juan Luis and Marguarita Feliciana CHOMBER), native of Jeremie on the island of Santo Domingo, sp. Juan Pedro ROUX, ca. 29 yr., i. Mar. 20, 1815 (SLC, F7, 289)

These New Orleans records are actually in Spanish themselves; these abstracts are translated. Her name was actually Marguerite Adelaide Augustine Renee, quite a mouthful. Her parents names were Jean Louis Robin and Marguerite Felicienne Chomberg or Chomber. Marguerite was born in Jeremie, Saint-Domingue. She died in 1815 at age 29, so she must have been born about 1786. I wondered if I might be able to find a record of her birth in Jeremie.

So I asked ANOM to show me the annual tables of births available for Jeremie.

There are more records available than there are annual tables. The annual tables are indexes to the registers, but not every register has one. Luckily, indexes do exist for the years that Marguerite was likely to have been born. This means I don’t have to go through every single record one by one for every year she may have been born in and can hopefully just find her in the index and know where to go.

I opened up the 1786 annual table and—voila!—there’s a name there that looks like it could be referring to my person! Now I know that I can expect to find a record for Marie Adelaide Renee Robin in the register for 1786 and can peruse it with confidence, knowing I should be able to find what I seek.

If I change my search to be for “Births”, what actually comes back is a bunch of annual registers of all acts, which includes marriages and deaths as well as births. They are in chronological order and divided up by year. The index is in order, which helps me locate the baptismal record I’m looking for on the fifth image of the 1786 register.

This entry spans two pages, here’s the second half:

Even without being able to speak French, I can see her parents’ names are Jean Louis Robin and Marguerite Felix Schoonberg. I’m on the right track! As it turns out, this baptismal record is actually for a sister of the person I started out looking for; the person I was looking for is here, too, but she was actually born in 1787. I only know that because I examined all the available indices looking for people with this surname. The sisters’ names are quite similar, but there is an entry in 1787 for Marguerite Adelaide Augustine Renee Robin that is separate from this one for Marie Adelaide Renee Robin. In any case, this is the process that was followed. Now I want to know what the rest of the entry says, because I can probably glean more information from it.

First thing to try: snip snip a screenshot and paste it into Google Translate, of course. This is the output:

Is it perfect? Definitely not. Can I understand the general structure and purpose of this document with the translation I got? Absolutely. If you copy a screenshot of text in another language that is printed vs. handwritten, you tend to get better results. It’s much easier for the computer to read printed words, just like it’s easier for us.

Let’s say I want to make sure I understand every single word in this entry and nothing is lost in translation. To achieve that, I am going to have to do the tedious part; typing the text as I see it into the text part of Google Translate. Luckily, and I can’t stress this enough—Google Translate is incredibly forgiving. It doesn’t matter if you aren’t really quite sure what the handwriting says; it’s very hard to be sure when you’re attempting to transcribe a language you’re not familiar with. But what I have found is that if I just type my best guesses in, the vast majority of the time, what I meant is inferred regardless of my egregious spelling mistakes, and I can actually use the output to see what the word(s) I misinterpreted were and revise my input to get a clearer translation. Google will also make suggestions when it thinks you made a typo and it knows what you meant, and you can use that to correct your input. So don’t worry about whether or not what you are typing is correct or makes sense. Just do your best and see what happens.

My input isn’t perfect. I can pick out errors I made myself—for example, where I have entered “fieu Jean Louis Robin” the actual word before his name was “sieur”. I’m sure there are copious spelling errors, and as I was typing, I actually corrected several of my interpretations of the handwriting myself because I could tell something was wrong by the out-of-place word that popped up in the translation where I knew it should say something about a baptism, and it was obvious when I had it right. I believe the district they resided in was actually Anse du Clerc, which I found by Googling “l’anse du clair st. domingue” because I thought the writing said that and it was close enough to get me to the right answer. The word that was translated as “Thursday” is one I wasn’t sure about, but upon reflection I think it actually says “Fevrier” for February. That makes sense, because this entry is towards the beginning of the register, just like February is towards the beginning of the year. Since I know this register is in chronological order, I can feel pretty confident now that I have it right.

So now, because I took the time to translate this French document even though I don’t know French, I have learned the following information about Marie Adelaide Renee Robin:

She was born on 2 Feb 1786 and baptized the next day

Her parents lived in Anse du Clerc, Jeremie

Her paternal uncle and godfather was Rene Robin, major commander of the battalion of the militias of Grand Anse

Her godmother and sister was named Marie Elizabeth Louise Robin

That’s a lot of information I would definitely want to have! This is why it’s important to examine the original documents yourself. Many published abstracts of these sorts of records do not include things like the godparents’ names and descriptions, but in this case that information includes details on familial relationships and gives me new people and places to continue my research with.

So that’s my general process. I start with a screenshot translation to get a general idea of what I’m looking at, and if it’s not precise enough for my purposes or the handwriting is too hard for the computer to parse, I then go through the more-tedious process of typing what I see and revising that until I have a translation that makes sense to me. I actually trust my own translations using this method more than I trust published translations of the same documents. If something doesn’t seem right to me, I can research the confusing parts until it makes sense to me, and I don’t have to rely on someone else’s translation (and handwriting interpretation skills) for my understanding of the document because I understand it myself. My French vocabulary has rapidly expanded by doing this a lot, to the point I can now understand many documents without assistance. There are only so many unique words that tend to show up in the same types of documents, after all.

I didn’t realize how much my French skills had improved until I recently had to work with some Spanish documents for the first time in awhile. Unlike French, I did study Spanish for a few years in high school. Generally, out of all the languages I’m not at all fluent in but might want to read a document written in, Spanish has traditionally been the least intimidating to me. But now that I have spent more time recently working on French stuff, I find French easier to understand. C’est la vie. It’s okay! It just takes practice.

There’s a similar type of archival website for Spanish colonial documents that is even more comprehensive than ANOM, although perhaps not as easy to navigate. It is the Spanish Archives Portal (PARES). I only just found this the other day and I am so excited. Louisiana was Spain for a long time, and so much of the documentation produced during the Spanish regime is catalogued and digitized here. There’s a detailed catalog entry for the Cuban Papers, which are held by the Spanish archives, as well; I am hopeful that soon all of that will be digitized, as it seems that Spain is well on its way to achieving that goal. I will use another real example to show how to use the site.

There was a French guy named Pedro Gautier who I know had a sugar plantation in Puerto Rico and died there in 1823. I don’t know if he’s related to me, but there’s a very decent chance he is, and I wanted to learn more about him. I have not had an easy time doing that up to now; I have found it difficult to locate Puerto Rican records and trees to consult. Well, I found them! Puerto Rico was a Spanish colony until 1898. And Spain was notoriously paranoid and kept tabs on pretty much everyone. Thanks, Spain!

I entered “pedro gautier” (with the quotes!) into the search box on the PARES site. This was the first result:

Because I am lazy, I copy and pasted the description into Google.

Well, that is interesting! I already have learned a few new things about “Pedro Gautier” (his name was really Pierre, being French and all). Namely, he had several daughters, one named Isabel/Elizabeth and married to a guy named Carlos/Charles Sauvage. I also learned that Pierre was a naturalized Spanish citizen.

I opened up the document image and it’s a 244-page PDF file, all in Spanish and all handwritten. Yes, it was intimidating. No, I was not excited about trying to find the relevant part. But actually, a lot of those 244 pages were blank, and more of them were duplicates of each other. So it wasn’t really 244 pages I needed to scan. Honestly, I just went to random pages until I noticed “Pedro Gautier” and went from there. It didn’t take that long to find him, and I didn’t want to go one by one because…well…it’s a 244 page PDF file. It would probably be better to be a bit more methodical, but whatever. I think I ended up starting at the end of the document, because the most relevant stuff I found started on image number 239, and I definitely didn’t go through all of that before finding anything interesting.

I can see relevant names and places in there without translating anything. I saw enough to know that I wanted to know what the rest of this says. This is the translation I ended up with for the first part of this document, following the same process I followed for the French baptismal register.

Don Carlos Sauvage, resident in France, husband of Doña Ysabel Gautier, and guardian of his sisters-in-law Doña Josefa and Doña Luisa Gautier, natives of the island of Puerto Rico, informs Your Excellency that his father-in-law Don Pedro Gautier, naturalized Spaniard, died on said island in 1823, and his wife Doña Feliciana Rumeau, born in the Spanish part of Santo Domingo, also died in 1827, having both come to establish themselves in Puerto Rico with their own land, finally establishing their domicile in the town of Ponce, where they bought land and also dedicated themselves to the import and export trade.

The gist of this 244-page behemoth is this: Gautier’s three daughters all went back to France after he died and were living in the Bordeaux region. The oldest one, Elizabeth, was married, and the younger two were meant to be getting an education. The problem was that the Puerto Rican colonial officials were trying to extract a heavy 15% tax in order for them to be able to access their inheritance, viewing them as foreigners extracting wealth from Puerto Rico. Their property had been sequestered. However, as all three sisters were born in Puerto Rico, and their parents were naturalized Spanish citizens, they were not meant to be subjected to such punitive fees just because they happened to be in France at the moment. Elizabeth’s husband was petitioning to have the 15% requirement waived in their case so they could have funds to support themselves and pay for their schooling.

This document gave me a lot more to work with than I had before; now I can go look for more information about all of these people. I didn’t know that Pierre was from Bordeaux, who his wife was, that she was from Santo Domingo and died in 1827, that he had three daughters, that those daughters at some point returned to France… you get the idea. It’s given me an “in” to do further research on this family.

I can’t talk about PARES without showing you at least one of the many cool old maps and plans I found in there just browsing. One thing to be aware of when entering search queries in PARES: you need to query in Spanish. So if you want to search for Louisiana, type “Luisiana” for best results. For New Orleans, type “Nueva Orleans” etc.

This is a map that shows the blocks in New Orleans that were affected by the Great New Orleans Fire of 1794. This map also shows the entirety of the city as it existed at that time; at the center bottom, where the number 3 is, is modern-day Jackson Square. The Spaniards called it the Plaza de Armas.

I thought that was so cool. There are tons of old maps available on there; some of them show the names of the original landowners at different places. I found some of my ancestors from the Canary Islands named, on maps showing the original layout of the settlements they occupied.

I also found some documents relating to the pirate Jean Lafitte.

This is a letter that was written to inform Spanish officials of Jean Lafitte’s plans to create a settlement at Galveston.

The bulk of the records I most want to see in the Spanish archives are probably included in the Cuban Papers. These have been microfilmed at least partially and are available at some libraries, but they have not been completely digitized yet. I am really hoping that will happen soon. Reading over the catalog descriptions had my mouth watering. Original censuses from the Spanish period. Service records for soldiers. Passports and emigration records. Documents from the hospital at New Orleans. Documents relating to enslaved people. Files of intelligence gathered on various people that Spain thought might be colluding against them. On and on and on. I think that soon we will have all of this available at our fingertips. What a time to be alive! My recommendation is that you start getting comfortable working in other languages now to prepare. ;-)

I want to close this out by mentioning again something that I have brought up before in passing, I’m sure. It highlights how limiting it can be to not consult sources just because they’re not in a language you are familiar with, and how much new information can open up to you when you try it anyways.

I am talking about Wikipedia! We all use it, it’s great for getting a quick overview on most any topic and for finding more sources to consult. I love it.

Well, Wikipedia exists in more languages than just English. And it may surprise you to learn that the Wikipedia sites in other languages are not just translations of English entries. They are entirely separate. I’m going to use the French example because that’s what I have most often used myself.

French Wikipedia includes many articles that have no English equivalent at all, and many times, even if an article does exist in English, the English version has far less information on it. (I’m sure the reverse is true as well.) You can find sources (yes, they’re often in French) that you would never have found otherwise by looking at the citations. Here’s a personal example: my mom’s maiden name is Marceaux. All Marceaux descend from a guy named Francois Marceau who emigrated from France to Louisiana in the late 1700s. Marceau came from a notable family. His uncle was General Francois Severin Marceau, a famed military figure from the French Revolution with monuments honoring him in Paris and everything. Pretty cool! The English Wiki entry I linked is okay, but look at the French one. It’s way longer and includes a lot of details that the English version doesn’t, as well as lots of new sources to check out. Reading it is fairly easy thanks to the automatic translations provided by Chrome.

From his French Wiki entry, I found that my ancestor had two more close relatives (and aunt and an uncle) notable enough to merit their own Wikipedia pages.

Émira Marceau was a famous artist; an engraver. I learned a lot about the Marceau family in France by reading about her life. There’s even a portrait of her, done by her husband, who also has his own Wikipedia entry.

The uncle was Auguste Marceau. He was in the navy and traveled all over the world. Some tidbits from his entry:

He took part in the Madagascar campaign of 1829 , which earned him the Legion of Honour . In 1832, he took part in the scientific expedition that brought the Luxor Obelisk back to Paris. He then took part in the Senegal campaign.

…

He radiated in the area for three years where he almost fell into a trap set by cannibals.

These are just the default translations my browser provides automatically, and I would need to learn a lot more to be able to really understand what this guy is famous for and what he was involved in, but this Wikipedia entry definitely has enough information to pique my interest. Cannibals?! There must be sources available documenting this guy’s adventures for the page to exist. And now I know that and can go look for them, starting at the bottom of that Wiki page.

Neither Émira nor Auguste are on English Wikipedia at all.

In fact, there’s an entire French-language genealogy portal on Wikipedia. There is no English equivalent. It’s amazing and I’m very jealous, but happy to have found it. You can find articles about many families in France. Anybody who was even slightly notable and had something to do with France or French people is worth checking for. Even the French entry for someone like Daniel Clark, an Irish immigrant to the United States and a politician and very wealthy businessman in New Orleans around the time of the Louisiana Purchase, who never set foot in France as far as I know, is more detailed.

Okay, that’s all I’ve got about this for now. I’m excited that my linguistics degree is finally coming in handy for something! I love languages. I hope I can help someone else to feel comfortable at least attempting to work in a language not their own; it’s very much possible and so worth the effort! It doesn’t have to be a barrier.

Awesome work, you’ve completely blown my mind.

I didn't know about using screenshots in Google Translate. I've got to try it. Sadly, some of the handwritten stuff is so bad, I can only make out a few letters. I recommend the FamilySearch word lists. I'll search for the combination of letters I can make out and often a word triggers my brain and I can see it in the handwriting and wonder how I could have missed it. https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Spanish_Genealogical_Word_List