Yesterday, I was looking at a FamilySearch profile I’ve been occasionally adding to, reviewing the sources I had previously attached. I didn’t feel like I really had enough to write up a Wikitree profile at the time I started working on it, but I was thinking it might be a good time to go ahead and do that.

The profile is for “Pedro” Gautier, a Frenchman who managed and later owned sugar plantations in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in the 1810s and early 1820s. I can’t identify him completely and do not know who his parents were or where, specifically, he was before his arrival in Ponce, but I have nevertheless managed to collect quite a few tidbits about him and his family.

As I was reviewing the sources I had dumped on FamilySearch related to Pedro, a familiar name suddenly jumped out at me. This is a passage from Sugar and Slavery In Puerto Rico: the Plantation Economy of Ponce, 1800-1850, by Francisco Scarano. I actually had initially landed somehow on an earlier draft version of Scarano’s work by Googling for information about Pedro Gautier. I looked him up and found his email address on the website of the University of Wisconsin, where he is a professor, and he very kindly pointed me to the final published version, which is available as an e-book and was accessible to me through my alma mater’s library.

[Hacienda] Quemado soon prospered under Gutiérrez del Arroyo; by 1805 it was reportedly worth 26,000 pesos, an unusually high value for a Puerto Rican rural estate at the time.* Upon his assignment to a high ecclesiastical post in San Juan, Gutiérrez del Arroyo left the estate under the management of a Frenchman, Pedro Gautier, who oversaw its transformation into one of the largest and most profitable plantations in the island in the decade between 1810 and 1820.

Gutiérrez del Arroyo is not a name that stuck out to me when I first read through this source, but when I came back after some time had passed, I remembered seeing it somewhere else recently. Not too long ago, I was fishing in the Archdiocese of New Orleans records. I searched for “Puerto Rico” in each volume that has been released as a searchable PDF just to see what would come up and who in early New Orleans had ties to Puerto Rico. I didn’t get many hits at all, but most of the hits were baptisms for the children of a guy named Francisco Gutiérrez del Arroyo, for example:

Maria Angela Eleonor (Francisco, native of Puerto Rico, official in the accounting office for the army and royal household, and Genoveba MASICOT, native of this city), b. Jul. 18, 1797, bn. Sep. 4, 1796, pgp. Francisco DE ARROYO, native of Santander in the Kingdom of Spain, and Baltasara DELGADO, native of Puerto Rico, mgp. Santiago MASICOT and Genoveba GRESBENBERG, natives of this parish, s. Carlos MASICOT and Jacinta MASICOT infant's uncle and aunt (SLC B14 38)

So then I started to get excited, because here’s a possible connection to Louisiana, for the very man Pedro Gautier worked for in Ponce. As it turns out, Francisco’s brother, José Nazario Gutiérrez del Arroyo, was the owner of Hacienda Quemado. I never did get around to writing a Wikitree profile for Pedro Gautier (yet), because I got sucked into learning about his one-time boss, who ended up being very interesting in his own right. The rabbit hole strikes again.😂

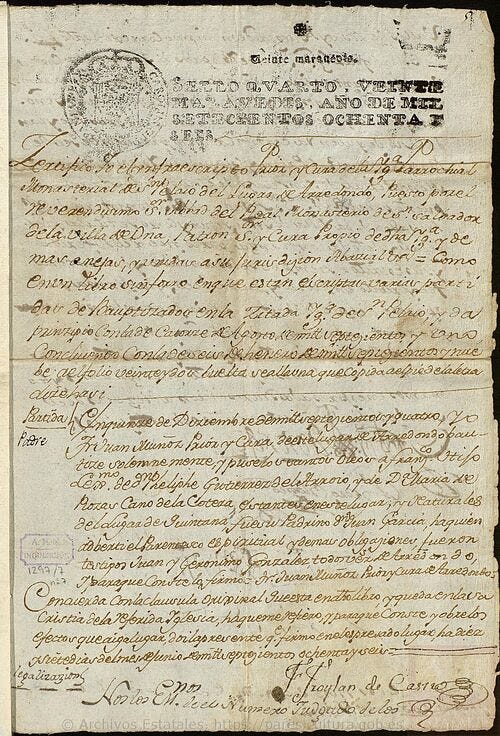

I started out by searching for “Gutiérrez del Arroyo” in PARES, the Spanish archive portal. I almost immediately hit genealogist paydirt. You don’t have to understand Spanish to guess that this document must be full of exactly the sorts of details I’m always on the hunt for. It is literally titled “genealogical information of José Nazario Gutiérrez del Arroyo”.

The scanned document is 80 pages long and written in handwriting that is reasonably legible, but unfamiliar enough that transcribing and translating the entire thing felt really daunting. But the contents were so interesting that I had to press on. (I didn’t translate every page, but I did review every page so I could tell which ones merited a full translation.)

This document was produced as José, a priest, was in the process of becoming a Spanish Inquisitor. He was actually the last Inquisitor ever appointed in Puerto Rico. In order to attain that position, it was necessary to prove “limpieza de sangre”, or blood purity. So the Spanish government would do these investigations into the person’s genealogy to prove they were qualified, and by so doing produced absolute genealogical goldmines such as this one.

There were three Inquisition tribunals held in Spanish America, in Lima, Mexico City, and Carthagena. The Carthagena tribunal was the one that should have handled José’s case, but the first few pages of this document are basically a long explanation of why it wasn’t feasible to do José’s investigation out of Carthagena. He was requesting that it be held, instead, in Madrid. José explained (in 1816) that due to a recent insurrection in Carthagena and the activities of various pirates in the Caribbean, communication between Puerto Rico and Carthagena had been cut off, and it would take at least a year to collect and disseminate the necessary documentation of his lineage to the tribunal in Carthagena as a result of the unrest. José’s paternal family was from Spain, so the documentation related to that side was easily available in Madrid, and José hoped to expedite his Inquisitor application by furnishing the easily-available proof for his Spanish paternal side while he promised to provide the proof of his (Puerto Rico-born) mother’s line at a later time.

On page 7 of José’s file, there are concise genealogical summaries for José’s parents and both sets of grandparents. (Translation below.)

Genealogy of the priest Dr. Don José Nazario Gutiérrez del Arroyo y Delgado, dignity of cantor of the Holy Cathedral, church of San Juan de Puerto Rico, who was born and baptized in said church on August 2, 1757.

Parents:

Don Francisco Gutiérrez del Arroyo, born and baptized in the town of Arredondo, in its monastic parish church of San Pelayo, abbey of the Royal Monastery of San Salvador de la Villa de Uña, on December 15, 1704; and his legitimate wife Doña Baltasara Delgado, married and baptized in the cathedral church of Puerto Rico, on the day and year that will be found on the documentation to follow.

Paternal grandparents:

Don Felipe Gutiérrez del Arroyo was born and baptized in the town of Balcasa, Soba Valley, on May 6, 1666, legitimate son of Don Juan Gutiérrez del Arroyo and Dona Juana Luz del Rivero; and his legitimate wife Dona Maria Santos de Rozas y Cano, who was born on October 23, 1687, and was baptized in the town of Ogarrio in the Ruesga Valley, legitimate daughter of Pedro de Rozas, and of Maria Santos Cano his wife.

Maternal grandparents:

Don Julian Delgado was born and baptized in the cathedral church of Puerto Rico, on the day to be found on the documentation to follow, legitimate son of the parents who will be named on documentation to follow; his legitimate wife Dona Feliciana del Rosario Ochain, born and baptized in the same cathedral, legitimate daughter as proven by the documents to follow.

The contrast between how José describes his paternal and maternal sides is striking. He has specific names and dates going back to the mid-1600s for his Spanish father’s side, but no dates at all and no names for great-grandparents on his Puerto Rican mother’s side. If his mother and grandparents were baptized in the same cathedral José was baptized in, in Puerto Rico, why was the documentation not available?

As I continued through the document, I found more genealogical treasures. There are official copies of the church registers in Spain showing the baptisms of José’s father and paternal grandparents. This one is the 1704 baptism of José’s dad.

There’s also a form included that contains questions and general instructions for the people conducting the investigation. These questions were to be answered by twelve credible witnesses to verify the truth of José’s claims to legitimacy under the rules of the Spanish Inquisition. In addition to the “pure blood” requirements, questions were asked about the nature of José’s professional work; if he had ever been employed in a “vexatious or mechanical” trade, he would be disqualified. Inquisitors were expected to be members of the noble class; if he worked with his hands for a living, that would disqualify him.

The interrogations of the twelve witnesses are also included in the file, but they are more interesting for what they don’t contain than for what they do contain. Each of the twelve witnesses attested to the validity of José’s paternal side only. Not a peep was made regarding José’s mother’s line throughout.

Of special interest to me, personally, was the 28-year-old witness who was a native of Puerto Rico, in 1816 residing in Spain, named Antonio Gautier. I do have an educated guess as to the identity of this person, but he raises as many questions as answers for me, so I will have to deep dive on him and his (possible) family in a future post.

In any case, José’s application was quickly approved by the King, and he became the last Spanish Inquisitor appointed in Puerto Rico. He never did, as far as I can tell, have to prove his maternal lineage, riding off the renown of his illustrious Spanish paternal side to skate on through the seemingly-stringent requirements of the Inquisition. To me, it seems like the Spanish authorities must have been willfully looking the other way here. It’s obvious to me that he’s dodging questions about his maternal side because he can’t prove his “limpieza de sangre” on her side. The most likely reason for that is that his mother wasn’t 100% Spanish at all, and had indigenous or African ancestry or both. But apparently there was at least some flexibility even for something as rigid as the appointment of a Spanish Inquisitor at this time. It’s really fascinating!

José’s sugar plantation, Hacienda Quemado, was the largest plantation on the whole island of Puerto Rico in its heyday, with over 100 slaves. At this time, most plantations in Puerto Rico operated on a much smaller scale. José’s was definitely an outlier.

Another interesting aspect of Hacienda Quemado is that José repeatedly hired Frenchmen to manage his plantation. Pedro Gautier, of course, was the manager for some time, and he eventually became part owner of the hacienda after successfully expanding operations. From Scarano’s book:

After Gautier’s death Quemado continued to thrive under the management of another Frenchman, José Maria Latour, and by 1827 it was the second-largest estate in the district in terms of slaveholding, and possibly still the largest in terms of output. In the early 1830s Flinter considered it a model of the high productivity of Puerto Rican haciendas. "The estate of the archdean of the cathedral," he wrote, "which has been many years established, has for fifteen years successively produced upwards of 5,000 quintals {250 tons], with only ninety acres under cane; and some years it has produced 8,000 quintals and upwards. This estate is situated on the best lands near Ponce." Shortly thereafter a management contract between Gutiérrez del Arroyo and Juan Lambert, a French emigré, described Quemado as possessing 114 slaves, two large animal-powered mills, an impressive array of sugar houses, slave quarters, a hospital, and a spacious house for the administrator, in addition to an undetermined expanse of cane fields and plantain groves (plantains were a staple in the slaves’ diet).

This was all happening not too long after the Haitian Revolution and the expulsion of the French from Saint-Domingue. It seems to me that José may well have been hiring Frenchmen from Saint-Domingue to run his plantation, and they were operating it using the Saint-Domingue model of plantation management rather than according to Puerto Rican norms. But I still need to see what else I can learn about Latour and Lambert to be able to confirm that hypothesis. I have conflicting information about Pedro Gautier’s origins, but he probably came from another Caribbean colony prior to arriving in Puerto Rico around 1805. He may have left Saint-Domingue and gone to Guadeloupe or St. Thomas before heading to Puerto Rico.

The group of people with connections to both Puerto Rico and New Orleans at this time seems to have been a small one. So far, every single person I have found who meets that criteria has been connected to the rest of the group in some way. I’m excited to see what else can be uncovered!

Fascinating, great work, as always.

I’m bowled over by your abilities in research and clear writing. Loved it!