Another day, another Laffite rabbit hole

When I go to write a narrative version of some story that I’ve uncovered, usually part of the goal is to make something complex into something that is easier for people to digest and understand. To make sense of all the disparate threads and various connections I’ve uncovered and turn it from a soup of evidence into a story. A story often includes clear heroes and villains, there’s a clear narrative arc and, ideally, some larger point I am making by telling it. I build a mental model for the historical character or event I’m learning about as I’m researching, and then I share what I’ve come up with, hopefully in an entertaining way.

Some stories, however, are so big or so complex that they defy my efforts to tidy them up and put them into a nice narrative with all the loose ends tied up. Every time I think I’m starting to “get it” something new comes up that makes me think I’m probably still missing something big. Or I can’t clearly see where the boundaries are between different groups at all, and generalizing becomes near impossible. It seems that the story gets more and more complicated the more I learn, instead of becoming clearer. I am not sure what the larger point is because it keeps shifting and transforming into something different every time I look at things from a different angle. The rabbit hole appears bottomless.

One such story for me is that of the Laffite pirates. I have written about them before, but the “point” I got from that earlier deep dive is that there is much we don’t know and much historians disagree about. It clarified more what is not known than what is. While I was working on that, I did some work on their Wikitree profiles, which were lovingly made by others long before I showed up, but which need a lot of TLC to separate facts from rumors and fiction. I ended up becoming co-manager of Jean Laffite’s profile with the intention of cleaning it up more once I had finished collecting all enough evidence to feel confident saying anything about them at all.

Since then, I have added notes to that profile to clarify what is truly known and what is not, and I’ve dropped various sources there as I’ve come across them so I (and others) could find them again later, but I haven’t yet felt capable of really doing the profile justice. But I come back to these pirates over and over again, and every time I look I find something new to complicate things. It’s always fascinating, but man, they might just be the grandaddy of all rabbit holes. No wonder so many researchers have been interested in them for so long.

I’m just going to take y’all along with me on a spiral I recently found myself in regarding the Laffites & co. This happens semi-regularly.

It didn’t start with me just deciding to research the Laffites that day. (It rarely does.) It started with me looking at my Puerto Rican DNA matches and doing different combinations of filters to see if I noticed anything interesting. One of the things I did, just to see, was filter the shared matches of one of my PR matches with whom I had many pages of people in common, by who had someone from Louisiana in their trees. (This is because it’s not possible, as far as I know, to enter multiple places into the main match list page filter. By using shared matches with someone from PR, I basically could take a subset of all my matches with PR in their tree and then filter those people by Louisiana.)

I did not find much, probably because the relevant ancestors lived a long time ago, too distant for most casual DNA test takers to have their trees built back that far. But I did find at least one person born in Louisiana who appeared in a couple of my Puerto Rican cousins’ trees. (This doesn’t imply that that person is our shared ancestor at all, by the way. I am simply trying to better understand the network of people who may have had connections to both places back in the Spanish period.)

The person I noticed was one Mathias Brugman Duliebre, apparently born in 1811 in New Orleans. He died in Puerto Rico. His father was named Pierre Brugman, and he was from Curaçao, a Dutch Caribbean island off the coast of Venezuela. His mother was from Port-au-Prince. This was the information I got from these matches’ trees, and I was able to confirm it by finding Mathias’s baptismal record in New Orleans.

So I went to see what else I could find about Mathias Brugman, and what do you know? He’s famous.

Mathias was an important figure in Puerto Rico’s fight for independence from Spain. He and his son were actually eventually executed for their revolutionary activity by Spanish authorities.

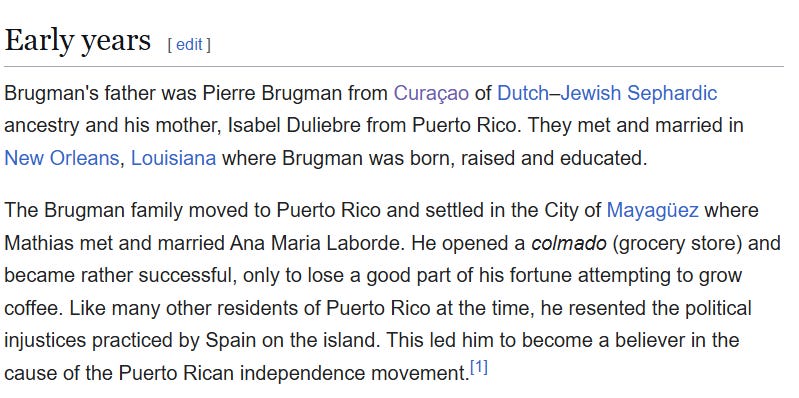

Wikipedia bios are often a good starting point for figuring out where to look for more information. This is what they have to say about Mathias’s early life:

A lot of trees also have Mathias’s mother from Puerto Rico, but the several church records in New Orleans that I’ve found all agree she was from Port-au-Prince, Saint-Domingue, not Puerto Rico. Her surname suggests French ancestry. Mathias’s eventual wife also had a French surname—Laborde. The church records in New Orleans agree about Pierre Brugman having been from Curaçao. Pierre Brugman’s parents were named Mathias Brugman and Louise Levy; his mother’s surname lends credence to Wikipedia’s claim that he had a Jewish background.

So then I started Googling various permutations of “Mathias Brugman” and “Pierre Brugman”. Imagine my surprise when the first result that came up on Google for “Pierre Brugman” was… Renato Beluche’s Wikipedia page.

Renato Beluche was one of the few famous Laffite pirates besides the brothers themselves. He was born in New Orleans and was a privateer/pirate ship captain for decades. He worked with the Laffites at Barataria and served in the Battle of New Orleans with the Baratarians. However, for most of his adult life, Beluche was heavily involved in the Colombian and Venezuelan independence movements along with the likes of Simon Bolivar. He was still captaining privateer ships and cruising for prize vessels, but with all the legitimacy and public veneration of a freedom fighter. 🤣 I could see how he may have had some connection to people from Curaçao. But why is Pierre Brugman mentioned on Beluche’s Wikipedia page?

This is funny because I worked out Beluche’s family connections using church records a long time ago. They’re definitely not the same guy. But, apparently, there have been serious attempts to prove that they were the same dude, and at least some people still believe it. What on Earth led to that conclusion?

A Beluche descendant wrote up a blog post that goes into this Beluche/Brugman theory.

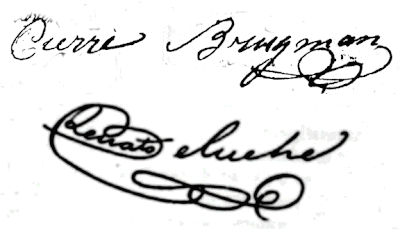

Perhaps the most debated, if not necessarily famous, argument for Renato Beluche quite literally being someone else comes from the family of Puerto Rican freedom fighter Mathias Brugman. As an example, some Brugman historians offer the comparison signatures of Pierre Brugman (top) and Renato Beluche (bottom) above. They note that the bold, looping Bs of both signatures seem too similar to have been written by different hands.

The signatures in question:

This is in no way convincing to me. The article continues:

The real confusion begins with a French letter of marque issued in March of 1810 for the brig L’Intrepide. The owner of the ship is listed as Joseph Sauvinet, a prominent New Orleans merchant and Laffite associate from the earliest days of Barataria. Her captain, according to Dr. De Grummond who is taking her information from legal documentation of the U.S. Navy, is named as Pierre Brugman. A description of Brugman, also in the ship’s papers, shows him to be a virtual twin of Beluche: He is thirty years old, five feet three inches tall and has brown hair. Probably the most arguable point in favor of this Captain Brugman being the revolutionary Mathias’s father is the birthplace he gives: Curacao.

This is hilarious. We are basing a theory that two different men were one dude on non-photographic, generic physical descriptions that would have applied to a multitude of people. About thirty years old, short, and brown hair. Must be the same guy! (The author of this article did not buy into this theory, either.)

I would suggest that if you are going to theorize that two people are one person, you first make sure that the other person didn’t have his own entire separate life.

I can shed a bit more light on some of the other connections drawn between the two. I dug around in the newspapers archives, and it appears that Pierre Brugman was also a privateer captain out of Barataria. At one point, he was the captain of l’Intrepide, which Beluche also captained. This does not imply they are the same person. Brugman and Beluche both captained many vessels throughout their lives. But they did probably know each other, and it would make sense if Brugman, too, was involved in South American revolutionary activities. His son, Mathias, certainly went on to become a revolutionary. Maybe the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

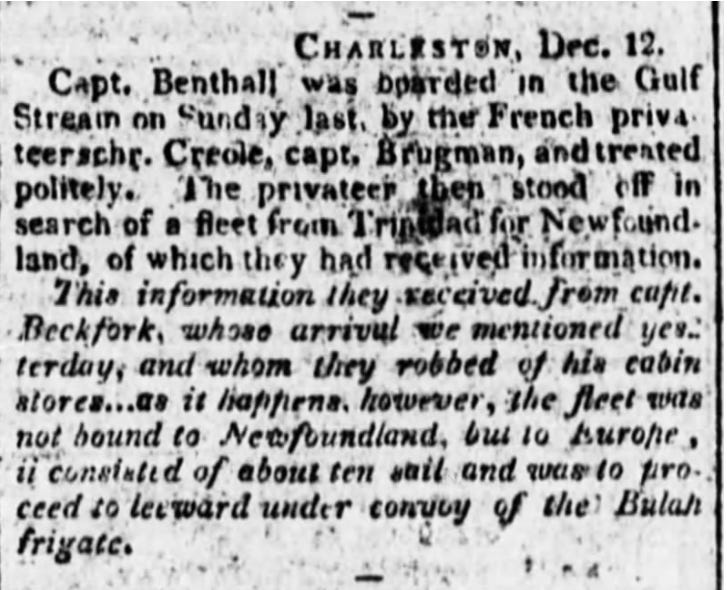

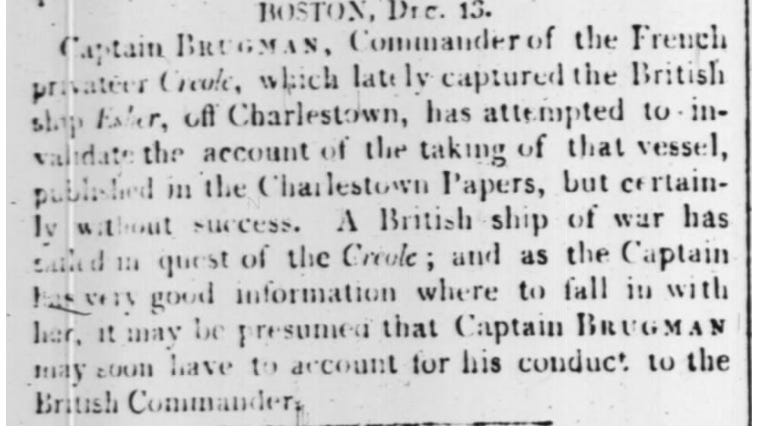

In 1805, “Capt. Brugman” was in charge of the Creole, a French privateer. Apparently, he treated his prisoners well enough.

Another blurb about the same capture was less generous.

In 1810, a newspaper article mentioned that the Duc de Montebello, a vessel of the “French freebooters”, was commanded by a “Broughman”. This article also mentions l’Intrepide and another vessel, la Petit Chance. It also mentions that Broughman had commanded l’Intrepide at times, a vessel known to have been commanded by Beluche at other times.

In 1816 “Pedro Brugman” commanded La Popa, a Carthagenian privateer.

The Laffites were known to have obtained letters of marque (permission to act as privateers) from the fledgling Carthagena (Colombia) government, who were interested in help from anyone willing to work against the interests of Spain. This gave at least a veneer of legitimacy, as the only difference between a privateer and a pirate was whether or not some government sanctioned your actions against another government with whom they were currently at war.

Back in 1813, Beluche was in command of la Popa.

Beluche appears in various articles throughout this time period and the decades following it with regularity, always as a privateer captain, and increasingly in his capacity as an important leader in the Venezuelan military. He almost certainly knew Brugman in some capacity; they captained the same vessels at different times. Neither ever captained the same vessel for extended periods; there’s nothing weird at all about different people having served in that capacity on the same vessels over time. Brugman and Beluche were likely hired to perform the duty of captaining these vessels for some set period of time.

So, switching gears a bit, let’s go back to that 1810 article. It had some interesting information in it other than the brief mention of “Broughman”.

“A system of iniquity which has heretofore been unparalleled to this country.”

“There appears to be a regularly connected chain of villainy…”

“We suspect extremely many persons being engaged who now share our hospitality and all the rights of American citizens…”

Sure, this is absolutely newspaper catastrophizing because it likely sold papers. However, the more I dig into these people, the more those statements start to feel like they aren’t really exaggerating very much at all. Just bear with me…

This particular article goes into quite a lot of detail about this “chain of villainy”. I think that the places called out are particularly illustrative.

The Duc de Montebello was fitted out at Baltimore, purchased by a Captain White, cleared out with French passengers for St. Bartholomews, was called the Amiable, put into Savannah (Georgia) armed, shipped part of her crew, sailed and received the rest from on board a vessel commanded by Capt. Kuhn. She assumed off the bar of Charleston the French character and name she now wears; sailed on a cruize, robs, sinks, burns and destroys every American, Spanish and English vessel she falls in with until glutted with plunder, she is compelled to put into this port [meaning New Orleans] under pretense of distress; her captain’s name is Basson; her apparent owner’s name Brouard—one Menton, and a certain John de Loupe, make conspicuous figures on board of her.

Remember the Gaultiers and the O’Duhiggs from Saint-Domingue that I spent so much time following? This paragraph quite literally hits every city in the U.S. they went through. Baltimore, Savannah, Charleston, New Orleans. And perhaps this is neither here nor there, but their home in Saint-Domingue was even specifically mentioned in the context of privateering next to Beluche’s name. This is one of the previous articles from above:

“Tiberon” is where the Gaultiers had previously lived, at the westernmost extreme of the island of Hispaniola, just a stone’s throw from Jamaica. They didn’t live there anymore by this point; they would have been in either Savannah or New Orleans by then. But still.

Later on in that article it says:

We hear of a vessel that was purchased at Norfolk by some Frenchmen and sailed for Savannah, but stopped at Hampton where it was equipping in every respect for a privateer: this circumstance joined to the circumstance of the Montebello's having been equipped by a certain Mr. Jerome at Savannah. We are induced to believe New Orleans and Savannah are intended as the two principal places of rendezvous.

Coincidence? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

In 1818 a batch of documents relating chiefly to the issues faced by the governmental authorities regarding the Laffites and their men, who were by this time operating out of Galveston, were published. The first items are extracts from letters written in 1817 by Beverly Chew, collector of the Port of New Orleans, to the federal Secretary of the Treasury. Beverly Chew was a close associate of Daniel Clark while he was still alive. He was one of the men named to administer Clark’s estate and embroiled in the interminable legal disputes over it with Clark’s daughter, Myra.

This letter is long, so I am just going to pull out some particularly juicy bits. He is essentially telling the secretary of the treasury that the pirates are out of control in Galveston, there’s nothing he can really do about it, and they can’t say he didn’t let anybody know about the problem.

The establishment [at Galveston] was recently made there by a commodore Aury [Louis Aury], with a few small schooners from Aux Cayes [Saint-Domingue], manned, in a great measure, with refugees from Barrataria, and mulattoes. This establishment was reinforced by a few more men from different points of the coast of Louisiana, the most efficient part of them being principally marines, (Frenchmen or Italians,) who have been hanging loose upon society in and about New Orleans, in greater or smaller numbers, ever since the breaking up the establishment at Barrataria.

*******

Since they have been denied shelter in Port-au-Prince, they have no other asylum than Galveston.******

I have lately sent an inspector of confidence, to examine La Fourche from the Mississippi to the sea, and he reports it as thickly settled for 80 miles from the river, has 8 or 10 feet water, and 6 feet on the bar, at the month or entrance in the sea: there is no obstacle whatever to craft entering it from the sea, and ascending to the Mississippi, and trading freely as high up as they please.

******

Bartholomew Lafon of this place (who acted as secretary to the meeting of 15th April, copy of deliberation forwarded in my last) is mentioned as the governor of the new establishment near the Sabine [where the gang intended to hold illegally imported slaves as they thought it was out of the reach of American federal authorities].

It’s clear that although the base of operations may no longer have been Barataria, the goal was the same as ever: smuggle goods into Louisiana. Profit.

A list of people who signed a letter to Commodore Daniel Patterson complaining about the depredations against the vessels they owned was also published.

Commodore Patterson was the same naval officer who led the breakup of the Barataria encampment, before the Battle of New Orleans. I recognize more than one name on this list. Richard Relf was the other executor of Clark’s estate. Laurent Millaudon was a Plaquemines plantation owner whose unhappy business dealings with Jean Joseph Coiron, the husband of one of the Saint-Domingue Gaultiers, produced hundreds of pages of court documents.

Now, you would think that this list could be used as a way to sort of get an idea for who was with the pirates and who was against them. But…

In 1824 a dinner was given in honor of Beluche in New Orleans.

So here’s a whole group of people singing Beluche’s praises, and that group includes both Richard Relf, who was on the list of complainers in 1818, and Commodore Patterson, who had been tasking with breaking up the Barataria operations way back in 1814! Apparently, much can change in ten years. However, what did not change is Beluche’s occupation. Beluche was arrested and tried for piracy in Jamaica in 1818. (He was acquitted, of course.) He was accused at times of not doing what he did out of any sense of justice or passion for the revolution, but to enrich himself. His response seems to have basically been “So what if I’m in it for the money? I’m getting results, aren’t I?”

As late as 1848 Beluche seems to have been considered someone you call when you need some dirty work done.

That Spanish quote says: “Do you want me to be an assassin? Fine, I’ll be an assassin.” Apparently, to fulfill that promise, this general went for help from Beluche.

And yet all of these people who knew him or knew of him and his whole sordid past, and even actively worked against him or his comrades, decided to… throw him an honorary dinner for assisting the Venezuelan army? 🤣

I wanted to make sure that Commodore Patterson in 1814 and Commodore Patterson in 1824 would have been the same person. They were. His Wikipedia entry is perhaps conspicuously silent on any of his activities between the Battle of New Orleans and 1828, but after that he was still doing naval officer stuff.

But what really jumped out at me on Patterson’s Wiki profile was this:

Patterson’s grandfather was a 1C1R of Edward Livingston, whose plantation was next to Daniel Clark’s and Pierre Gautier’s in Plaquemines Parish. Their common ancestors were a Livingston who married a Schuyler. Edward Livingston, the one who orchestrated the pardon of the Baratarians for their War of 1812 service. The one whose wife was from Saint-Domingue.

Something something Henry Schuyler Thibodaux.

I can draw no conclusions from all of this. It truly often feels like everyone I look at is playing both sides in some way or masking their true motivations. No wonder I can’t stop trying to figure them out. 🤣

Another fabulous piece of digging for genealogical treasure! It's like you're going through a wormhole and about to emerge into another universe.

Came across a picture of Lafitte https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2017/april/twilight-gulf-coast-pirates I wouldn't want to cross him!

Great detective work as always. One thing I take from your work is that these movers and shakers from this time period did not want all of their tracks uncovered. I suspect that many dabbled in illegal activity at times. They were connected to the powerful families of the new U.S. government. You are bucking history in uncovering some of these facts. Two of my brick wall ancestors were of Spanish and Italian descent who I suspect to be sailors that probably jumped ship in New Orleans that potentially could have been part of these crews, but is probably impossible to prove. Great work as always.